May 27th, 2021 / Leave Feedback / nezuppal

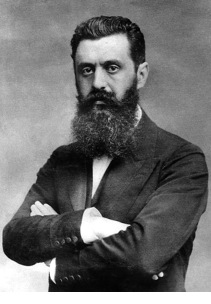

The early modern roots of the Zionist movement emerged from the persistent persecution of Jewish people across Europe since the Middle Ages, and across the globe long before that (Halperin, 2015). This persecution caused Jewish people to flee and disperse all across Europe and the Middle East in diaspora. Seeing this persecution and diaspora, many believed that people of the Jewish faith deserved their own land and their own government (Herzl, 1895; Weizmann, 2005). Theodore Herzl, one of the first Zionist thinkers towards the end of the 19th century and perhaps the most influential, planned to create a homeland for Jews to escape persecution in Europe. Since Herzl (1895) the creation of an Jewish homeland was indeed the main aim for every Zionist, with Eichler (2016) noting that ‘the official goal of the Zionist movement … a Jewish national home to be secured by international law.’

Another key aim of the Zionist movement was the ending of diaspora. The treatment of Jews during the 20th century was terrible and Herzl’s desire for a mass migration of Jews to the Middle East to end diaspora, referred to as Aliyah, took place in waves, with the first being between 1881 and 1903 (Greilsammer, 2011). After the devastating persecution during the Second World War the migration of Jews to Palestine increased massively; Weinstock (1973, p.55) commented that ‘fascism in Europe gave considerable impulse … at the end of the Second World War the 583,000 Jews represented 1/3 of the Palestine population.’ This continued immigration, purchasing of Arab land and refusal to allow Arabs to work on Jewish-owned land led to increased tensions between Jews and the surrounding Arab states.2 Heightening this rivalry, the day after the Israeli leader David Ben-Gurion declared independence for Israel a coalition of Arab forces invaded Israel. During the following ten months of fighting the Arab coalition eventually lost and was forced to retreat, with Israel taking control of the whole of Palestine and a large section of Transjordan, 60% more land than what they had been guaranteed by the United Nation’s (UN) partition plan. (Rogan, 2008, pp.102-103).

The Zionist movement was certainly successful in creating a Jewish homeland, which became an internationally recognised sovereign state. However, the Zionist movement undeniably failed in achieving some of its original objectives. Herzl envisaged a ‘model’ society based on equality between Jews and Palestinian Arabs, as Karsh (2006, p.470) notes that ‘the archives show that rather than seek the expulsion of the Palestinian Arabs, the Zionist leaders believed that there was sufficient room in Palestine for both peoples to live side by side in peace and equality.’ After the 1948 war hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees were scattered across the Middle East and many were not allowed to remain in Israel (Eichler, 2016). This poor treatment and eradication of the local population was certainly not what Herzl and Weizmann had envisaged and did not reflect the desired ‘model’ citizen or society (Halperin, 2015). Herzl had repeatedly stated that ‘Arabs and Jewish immigrants could live and work together in harmony’ and that there would be no need for Arab expulsion (Karsh, 2006, pp.468-469).

Nevertheless, no one can deny that Zionist movement did achieve a few key objectives and there are a number of reasons for these successes in 1948. Support from the West, particularly the USA and the UN, was vital in securing their independence. Moreover, Britain’s withdrawal from the region and their simultaneous problems with India and Pakistan gaining independence meant that support for the Arab cause dwindled after the Second World War. Furthermore, Israel’s superior financial situation, technology and international support meant they were able to win the 1948 war and secure a sovereign state for themselves.

The primary Zionist objective was to create an internationally-recognised national home for Jewish people; Weinstock (1973, p.51) notes that when Herzl ‘convened the first Zionist Congress at Basle in 1897’ he described the Zionist aim ‘as being the establishment for Jewish people of a home in Palestine secured by public law.’ Certainly, this was achieved first with the UN Resolution 181 in 1947 which guaranteed a partition plan but was then further emphasised by David Ben-Gurion’s declaration of independence in May 1948. Moreover, Zionists also wanted to see ‘the revival of the Hebrew language and culture’ and saw this ‘as one of the essential elements of a new society’ (Greilsammer, 2011, p.43).

Indeed, there can be little debate about the success of Zionism with regards to this particular aspect of their objectives. Conforti (2011, p.572-573) reaffirms this success by analysing the UN’s actions after the British withdrawal from the region, concluding that ‘from the legal point of view, the resolution of November 1947 that decided the division of Palestine in a Jewish and an Arab state was the international community’s (UN and USA) endorsement of the creation of Israel’. However, the creation of a Jewish national home was not supposed to come at the expense of the Palestinian population. Numerous times, Herzl and other key Zionist leaders expressed their desire to share the land with Arab Palestinians. After analysing Herzl’s works, Karsh (2006, p.471) concludes that ‘there was no trace of such a belief (that Arabs should be expelled to allow Jews to enter Palestine) in either Herzl’s famous political treatise The Jewish State (1896) or his 1902 Zionist novel Altneuland (Old-New Land).’

Several political leaders shared this idea of peaceful co-habitation with the Arab population. Indeed, as early as 1934, ‘Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Party prepared a draft constitution for Jewish Palestine, which put the Arab minority on an equal footing with its Jewish counterpart ‘throughout all sectors of the country’s public life’ (Karsh, 2006, p.473). Thus, the apparent success in 1948 of creating an internationally recognised Jewish state is undoubtedly tainted by the fact that this came at the expense of thousands Jewish and Arab lives and created a high level of animosity between the Jewish population in Israel and the surrounding Arab nations. The creation of the state was, as Greilsammer (1973, p.50) puts it ‘on some levels, an incredible success’.

The success of the Zionists in creating a nation-state was due to a number of contributing factors and fortunate circumstances, including Western support, British withdrawal and Arab divisions. Eichler is perhaps the historian who places the most emphasis on Western aid benefitting Zionism, asking ‘how could we even think of the Zionist movement succeeding without support from Western colonial powers?’ (Eichler, 2016, p.8). After the end of the Second World War the British Empire was in full retreat and the British government could not afford to sustain its influence across the globe. This forced Britain to retreat further from the Balfour Declaration in 1917 and the Middle East in general. Moreover, Conforti (2011, p.570-571) astutely comments that ‘it (Israel) emerged at the same time as independent India and Pakistan, a time when the British Empire was crumbling, and the Zionist movement was able to take advantage of British weakness.’ Zionist leaders, sensing this withdrawal, used an ‘armed insurrection’ to ‘force the British to turn over the Palestine file to the UN’ (Eichler, 2016, p.8).

Also, the Zionists were able to achieve their objective of creating and securing a Jewish homeland because of divisions within the Arab League.3 Indeed, Rai (2014, p.2) notes that Zionists were successful in 1948 because ‘the Arab governments all pursued their own objectives, with King Abdullah of Transjordan willing to accept a Jewish state in return for territorial gains.’ These divisions were further compounded by the fact that the newly formed Israel was more unified, better equipped and more financially able to sustain a war (Weinstock, 1973) Indeed, Weinstock (1973, p.58) estimates that, in the 1940s, ‘the Arab industrial sector amounted at most to 10% of the global Palestinian industrial produce’ and that ‘in 1942 … Arab industry in Palestine consisted of 1,558 establishments engaging 8,804 persons.’ Weinstock (1973, p.58) therefore concludes that the Zionists were able to create and protect their sovereign state because they were ‘possessing technological and financial advantages.’ Thus, the Zionist movement was successful in achieving its main objective of an internationally-recognised Jewish homeland, just three years after the horrors of the Holocaust. However, this new state was not what a lot of original Zionists had envisioned. It did not allow Arabs and Jews to peacefully co-exist, as Herzl had originally intended (Rai, 2014).

Another objective of the Zionist movement, an extension of the creation of an internationally-recognised home, was to re-define the stereotypical Jewish man and create a model socialist society based on democracy, law and equality. It could be said that in 1947 and 1948 Israel failed to achieve this objective. As Greilsammer (2011, p.41) repeatedly states, a secondary key objective for Zionists was ‘to form a new Jewish man, strong, healthy and free, both typical and universal, to be an example for other nations.’ Indeed, Lustick (1980, pp.131-132) accurately notes that ‘most Zionist founders dreamt of a modern, pluralist, secular, democratic state’ before concluding that they failed in this objective and, in 1948, ‘Instead of creating a new Jew and a state built on mutual tolerance and respect for the Other, Israel fixed certain behaviours and perpetuated divisions.’ Thus, Israel did not represent the model society that many Zionists had dreamt of prior to Israel’s independence in 1948. Indeed, some historians consider the desire to create a model state with model citizens as admirable, but a complete failure in the case of Israel. Because the Zionist movement had elected Palestine as a place to establish their homeland, the economic realities of the region became clear quickly. David Ben-Gurion was unable to improve the economy as quickly as had been expected and ‘general austerity was the rule’ with ‘the power of the Labour Party becoming overwhelming and Ben-Gurion’s autocracy was insufferable for many’ (Davidson, 2002, p.24).

In fact, Greilsammer (2011, p.50) is especially critical of the failure of the Zionist movement to create a fair and modern state, commenting that ‘the gap between the ideal of the founders of Zionism and reality is even more striking as we consider the theme of ‘conquest of labor’ … and the desire to build a society where there would be no exploitation.’ The initial Zionist leaders expressed their desire to allow Arabs to continue living with the same rights that they had. It could even be claimed that Gurion was an idealist in the 1930s, as he claimed that this new Jewish state would have ‘one law for all residents, just rule, love of one’s neighbour, true equality. The Jewish state will be a role model to the world in its treatment of minorities and members of other nations. Law and justice will prevail in our state’ (Karsh, 2006, p.481).

However, the Zionist movement failed in this objective to create peace and harmony between Arabs who had lived in the region for generations and the newly created Jewish homeland. Herzl himself ‘did not envision the Jewish-Arab conflict’ (Eichler, 2016, p.6). Instead of the envisaged peaceful transition into a Jewish majority in Palestine, the 1948 war forced Israel to take a hard-line against any potential Arab enemies. This led to the creation of 700,000 Palestinian refugees. This brutal expulsion was not a reflection of the ‘future Jewish national home as an ideal society’ (Eichler, 2016, p.6). Whilst it is true that Israel remains a full democracy which respects both Palestinian Arabs and Jews, for example by having rules such as ‘in every Cabinet where the Prime Minister is a Jew, the vice-premiership shall be offered to an Arab and vice versa’ (Karsh, 2006, p.472), the political system has numerous inherent flaws. Glass (2001) comments that ‘Herzl did conceive of a diverse society’ and that ‘the Israeli political system in place over this time is a far cry from Herzl’s own vision.’ Thus, it is apparent that a key objective of the Zionist movement was to create a model society with model citizens that was fair and reflected the best practices of Western democracies. However, in 1948 its treatment of the Palestinian Arab population, combined with economic and social realities of governing such a new and impoverished state meant that Zionists ultimately failed to create a tolerant society and instead built a right-wing anti-Arab state; as Weinstock (1973, p. 43) concludes, ‘it is doubtful whether the founders of the Zionist movement would have relished this prospect.’

A third essential objective of the Zionist movement was to fully achieve an end to diaspora and group together all the persecuted Jews from across the globe in one nation to guarantee their safety. This was a goal right from the beginning as Jewish persecution was the essential reasoning for the necessity of a singular Jewish homeland in the first place. Indeed, Greilsammer (2011, p.41) states that ‘the first goal of this ideology was to end the Jewish Diaspora … and to bring them to Israel.’ Indeed, with regards to this particular goal the Zionist movement was extremely successful. The expansion of the Jewish community in Palestine was massive in the early 20th century, as the ‘Jewish population rose from 24,000 in 1882 to 175,000 in 1931’ (Weinstock, 1973, p. 55). These Aliyahs involved the emigration of Jews from all over the world, including Jews ‘from communist countries after de-Stalinization; Jews from Egypt; Jews from post-Soviet countries, and Ethiopian Jews’ (Greilsammer, 2011, p.45). This growth in population continued and was accelerated by the Second World War so that, by 1948, the Jewish population was close to 500,000. This was a massive increase in population but did not reflect the initial Zionist ideal of all Jews living in one state.

Indeed, it would be impossible for every single person of the Jewish faith to relocate to Israel; some have found accepting new homes in Britain or the USA whilst some others fear for their own safety if they were to move to the Middle East. Indeed, as Neff (1995, p.6) highlights, ‘some Jewish communities, such as the one in Alegria, are not moving to Israel, but to other countries.’ After the mass migrations which took place prior to 1948 the Zionist leadership began to accept that ‘the likelihood of mass migration again is extremely low’ (Greilsammer, 2011, p.46). Indeed, Ben-Gurion himself privately stated that ‘the idea of the Zionist ‘triumph’, a definitive end to the Diaspora, is not believable anymore’ (Jensehaugen, 2012, p.289). Moreover, Eichler (2016, p.6) notes that ‘Herzl accepted that ending diaspora was unlikely’ but he still aimed to gather a majority of Jews in one state so that ‘Jews who were left in the diaspora would be respected because now the Jews would be a normal people with a normal political homeland.’

Thus, it could be deemed that this objective was successful because the Zionist movement adapted their definition to fit reality; they became aware that not every Jew in the world would want to live in that particular part of the world (Jensehaugen, 2012). However, the leadership still accepted the importance and necessity to encourage Jewish migration, which was effective prior to 1948, so that the Jewish identity and pride could be re-established (Klocke, 2014). The Zionist movement was able to achieve this particular objective with relative ease due to the fact that Jews across Europe had been persecuted terribly for hundreds of years (Morris, 2009, pp. 82-87). This was exposed with events such as the Dreyfus Affair in France, or the Holocaust in Germany or the Pogroms in Eastern Europe (Zollman, 2002). It was not hard for Zionists to convince persecuted Jews to unite together under one sovereign state because many European Jews had first-hand experience of the horrific treatment they experienced in Europe (Jensehaugen, 2012).

Nevertheless, Weinstock (1973, p.53) does raise the important point that ‘it is thought that the wave of socialist Zionists (from Eastern Europe) were the main cause of hostility with the Arab population.’ The hostility towards these migrants came from Zionists as well as Arabs and ‘Russian Jews were considered by a number of Zionists and members of the Yishuv to constitute a major factor in arousing the hostility of the Palestinian Arabs’ (Weinstock, 1973, p.53). Thus, whilst the Zionist movement may have been as successful as possible in reducing Jewish diaspora around the globe, this may have made it a lot more difficult for Arabs to tolerate them and therefore reduced the success of some of the other Zionist goals. Thus, analysing the success of certain Zionist aims is extremely complex as they often overlap and success in one policy area can directly lead to failures in other areas.

In conclusion, it is difficult to assess the success of the Zionist movement in 1948 because it was ‘continually evolving and adapting during the first half of the 20th century’ (Conforti, 2011, p.570). Undeniably, the creation of a sovereign state in 1948 and a Jewish home which could unite any persecuted Jewish people from around the world was a huge success. Furthermore, the establishment of a democratic system and one of the finest legal systems in the world is no small achievement in such a short space of time, considering that mass Jewish migration into the region only really began in 1905 with the Second Aliyah (Morris, 2009, pp.142-144). However, the first Zionist leaders, such as Herzl or Weizmann, wanted to create a society that people around the world could aspire to. Indeed, there was no animosity towards the Palestinian Arabs in the early years of Zionism as the leaders felt that their presence in the region would be ‘beneficial’ (Weinstock, 1973, p.49). The Zionist movement, for the most part, genuinely believed that there would be enough space in Palestine for new Jewish immigrants and existing Arab citizens (Herzl, 1895).

After the 1948 war, however, a lot of these objectives completely failed. Hostilities between the Arab countries and Israel was extremely high, 700,000 Palestinian Arab refugees were displaced, and Israel became a right-wing autocratic state for a number of years in an attempt to boost its own economy (Margolick, 2008). However, as outlined by Herzl (1895) the main aims of the Zionist movement should always remain the creation of a Jewish homeland, the end of diaspora and the revival of Hebrew and Jewish culture. These key aims were achieved, to some extent, by the end of 1948.

Any successes that the Zionist movement enjoyed were down to a number of contributing factors. Most important of which was the support from the West (Rogan, 2008). Perhaps borne out of guilt from the atrocities of the Holocaust, or perhaps because the USA saw limitless benefits of having an allied democracy in the region, the West was very eager to support the Zionist movement (Rogan, 2008, pp.23-26). Britain’s withdrawal from the region and the takeover of the Palestine situation by the UN definitely benefitted the Zionist cause as it created the partition plan in 1947 and paved the way for a declaration of Israel’s independence in 1948 (Glass, 2001).

Moreover, the disunity between the surrounding Arab states and ‘their lack of wealth and infrastructure also made Zionist’s objectives easier to achieve’ (Karsh, 2006, p.479). Thus, the Zionist movement was successful in achieving their main aims in 1948 of ending diaspora and creating a sovereign Jewish state, but this success came at a price and that was the type of state they wanted to build. Israel in 1948 did not reflect the thinking of original Zionists who wanted Arabs and Jews to live side-by-side and wanted to build a model society (Rai, 2014).

A more nuanced conclusion would suggest that the Zionist movement was fairly successful in achieving its objectives in 1948 but this success caused problems later on with surrounding Arab states which has largely tainted the view political historians have on Zionism and its success.

One thought on “To what extent and why was the Zionist movement successful in achieving its objectives in 1948?”